- Home

- Nazli Eray

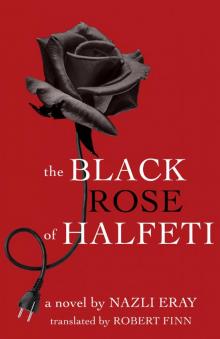

The Black Rose of Halfeti

The Black Rose of Halfeti Read online

Modern Middle East Literatures in Translation Series

the BLACK ROSE of HALFETI

a novel by NAZLI ERAY

translated by Robert Finn

CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES

The University of Texas at Austin

This English translation copyright © 2017 by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at The University of Texas at Austin.

All rights reserved

Cover image: Courtesy of iStock

Series Editor: Wendy E. Moore

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017932835

ISBN: 978-1-4773-1309-1

Originally published in Turkish as Halfeti’nin Siyah Gülü by Doğan Kitap in 2012.

Dear Madam,

I am madly in love with you. Maybe that is why I hold your hand in mine for so long and squeeze it so tightly. To feel your touch. I want to sleep with you. I want to make love to you, to make you mine. But Elfe must not hear of this in any way. If we are to make love, you should purchase a drug from a pharmacy. The name of the drug is Viagra. This will take place in your home, if you should be willing. I wait impatiently for that day, the day that you will be mine. My cell phone is 0535 361 77 13. Don’t use my home phone. Use this one. If I don’t answer, it means I can’t talk then. Please don’t get the Viagra from a pharmacy near your house. They won’t think well of you. Get it from another pharmacy. If I take this medicine, we’ll be very happy. Don’t forget to destroy this message, sweetheart.

THE SEYR-I MARDIN RESTAURANT

I am sitting on the top floor of the Seyr-i Mardin, looking out at enchanting Mesopotamia spread before me. This city has intoxicated me; I feel as though I had something to drink, but on the contrary, everything around me is perfectly measured, perfectly calm and quiet.

Up above on the hill, Mardin Castle looks out at the plain of Mesopotamia and beyond, as it has done so for centuries.

There’s a slight breeze blowing now; my hair flutters, and I readjust the black-framed sunglasses I am wearing.

Down below, a playful Arab tune jammed into a cassette player caresses my ears for a moment or two, then stops. Cut off. Mardin spreads out around me; I look out at this extraordinary city as though enchanted.

Silence.

The silence around me fills my head, making me dizzy. I want to walk some more in the narrow backstreets; I want to go up the nearby staircase and look down. I want to buy scented soap and never leave this city.

And actually, no one asked me, no one invited me here.

The city, silent and reticent, introverted, turned me with that strange energy it radiates into a fly fallen into a spider’s web and about to die.

The Seyr-i Mardin.

A high place. I climbed up so many flights of stairs to get here. A setting that offers the city and the plain of Mesopotamia to me where I sit.

I’m both content here and struggling inside that murky, sticky, thick spider web into which I have tumbled.

I suddenly realize that this spider web must be a storm in my soul, the expression of a precipice inside my brain. Mardin, lying here so peacefully with its stone houses, narrow streets, and cool, dark courtyards, has nothing to do with this.

The only thing it did do was turn me into a fly and make me fall into that spider trap that I sheltered inside me.

Now I’m struggling. I’m struggling inside myself.

I could die. I could die as I struggle.

I realize this. I have to be calmer. More calm.

I take a sip from the water in front of me.

I’m calmer now.

A thousand thoughts are passing through my mind.

I realize that I’m in love with Mardin. Whenever I struggle like a fly inside that spider web, I realize that I’m in love. A love so intense it’s as though it tore off my wings, broke my hairy fly legs, and blinded me. I can’t do a thing.

There is an ancient city before me. I know neither its language nor its geography. I just suddenly showed up here.

It takes me into the palm of its hand, makes me a captive. It won. It won’t let me go, let me escape from it . . .

Even though it’s so hot, I don’t want to leave the Seyr-i Mardin.

I scan Mesopotamia with my eyes as it stretches out in front of me, trying to capture something on the distant line of the horizon.

There’s nothing there.

Everything is peaceful and quiet.

That Arab music starts to sound again from somewhere down below.

It’s so playful, so lively!

I close my eyes and let myself go with the music for a moment. I relax a little.

I fell in love with a city of stone. There’s no one here I know, no place to go, nothing that belongs to me.

If the sun gets hotter, I’ll seek shelter in some courtyard and drink some more water.

I’m still listening to the music. The ancient stone city surrounds me. It seems to have taken me by the waist and is drawing me in.

“Let me learn a few streets, and find myself a hotel. A little restaurant, a store that sells soap . . . I have to find these,” I was thinking. “A mirror shop, and Shahmerans on mirrors . . . I have to find them. I should get myself a pendant. A silver ring!”

THE MIDNIGHT LETTER

I will not forget for the rest of my life that letter I received at midnight. It was nearly one A.M. in Ankara when I received that cry of longing and passion, that strange, demanding letter, that manifesto of desire. I held the little piece of paper in my trembling fingers, reading in astonishment the sentences written in an agitated and expansive script.

A few minutes before the letter arrived, the following conversation had taken place in the Ankara night:

Elfe spoke excitedly.

“I was in the room inside. I heard banging noises at the door. I took the gun out of the drawer and put a bullet in it. ‘Who’s there?’ I shouted. The racket at the door continued. Just then you called . . .”

“It was like I just felt an urge. That’s why I called. How are you?” I asked. “How are you?”

“There’s all this noise at the door. It could be a thief. Don’t hang up the phone.”

“Let me call the police.”

“I have a gun.”

“Please don’t take the gun out. I’m calling the police.”

I could hear Elfe speaking on the other end of the phone.

She must have opened the door.

“A, a . . . Doctor! Is that you? I almost shot you . . .”

“What’s going on, Elfe?” I shouted from the other end of the phone.

“The doctor came down from the apartment upstairs. He was the one banging on the door. It was hard to see him in the darkness. He came downstairs in his pajamas, the doctor,” said Elfe.

I heard the old doctor’s voice.

“Where? Where is she?” he asked. “I’m looking for her.”

“She’s not here. She’s in her own house,” Elfe said. “But she’s on the phone right now.”

“I’m worried, very worried about her,” the old doctor said. “I’m very worried about her,” he repeated.

“Talk to her, she’s on the phone.”

Elfe gave the phone to the doctor.

“Hello, Doctor Bey?” I said.

“Hello!” said the doctor. “I’m very worried, very worried about you.”

“Don’t worry, I’m in my house.”

“You weren’t here.”

“I’m at home now.”

“A letter,” the doctor whispered into the phone. “I wrote you a letter. I came to give it to you.”

“I’ll get it tomorrow morning.”

“I have to leave it tonight,” said the doctor. “But Elfe sh

ouldn’t see it.”

I was a little taken aback. The old doctor was Elfe’s upstairs neighbor.

“I left the letter in the box,” the doctor said. “The white box next to the door.”

I could hear the doctor pacing in the corridor.

“I left the letter in the white box,” he said. “Once you’ve read it, destroy it.”

He hung up the phone.

I was thinking, in the semidarkness of my room, What could it be?

I called Elfe again.

She picked up the phone.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Strange,” said Elfe. “The old doctor came downstairs; he was the one making the racket at the door. I took out the gun and opened the door. He saw the gun right away. After all, he’s a former soldier. He raised his hands in the air. He was asking for you. He was worried. That’s what he said. When he talked to you on the phone he seemed to relax a little. He came inside and walked about a little in the corridor. He had his pajamas on . . . I’ve never seen him like that. I brought him upstairs, to his apartment. His wife is old, and she must have been asleep. I didn’t see the caretaker. He left the door open when he came down.”

“Elfe, would you look in the white leather box in front of the mirror?”

“I’ll take a look; what’s there?” said Elfe.

She opened the box.

“There’s a piece of paper, a folded-up message here,” she said.

“Would you read it to me?”

“Sure.”

I listened to Elfe’s voice as it came from the other end of the phone.

Dear Madam,

I am madly in love with you. Maybe that is why I hold your hand in mine for so long and squeeze it so tightly. To feel your touch. I want to sleep with you. I want to make love to you, to make you mine. But Elfe must not hear of this in any way. If we are to make love, you should purchase a drug from a pharmacy. The name of the drug is Viagra. This will take place in your home, if you should be willing. I wait impatiently for that day, the day that you will be mine. My cell phone is 0535 361 77 13. Don’t use my home phone. Use this one. If I don’t answer, it means I can’t talk then. Please don’t get the Viagra from a pharmacy near your house. They won’t think well of you. Get it from another pharmacy. If I take this medicine, we’ll be very happy. Don’t forget to destroy this message, sweetheart.

The letter the old doctor had left in the box had ripped the Ankara night apart, as though into pieces; it had fallen like a bomb into that sensible, quiet, sleepy darkness of the city night.

I was confused.

The directness of the letter, the commanding tone, everything in it astonished me.

Elfe shouted: “What is this?” from the other end of the phone. “What the hell is this? How can this guy dare to do something like this? I’ll tell the building manager. I almost shot him. A lunatic!”

“Quiet,” I said. “Please don’t say anything to anyone. Nobody should hear about it. Hide the letter. I’ll look at it when I come tomorrow. He’s a very old man. He must be going through something . . .”

I hung up the phone.

I had no idea what to think, what I should do.

The darkness of that silent, tranquil, subdued Ankara night suddenly seemed to come alive.

For a minute it seemed like there were eyes looking at me through my bedroom curtains. I got up and went into the next room. In the living room, the plants with their green leaves seemed like they were awake. One leaf quivered slightly in the darkness. It had grown a little. It was getting ready for the morning.

I was thinking about the old doctor. His light blue eyes and the sharp lines of his face came before my eyes. I had seen very little of him. I was in a state of confusion.

Two months ago, when I was sitting in the living room, he had come down to Elfe’s apartment from the apartment upstairs with his wife.

THE OLD DOCTOR

“Allah, Allah,” Elfe whispered into my ear. “I’ve been living in this apartment for years. This is the first time that the doctor and his wife have come here, come downstairs. Last year the doctor made such a fuss just because I planted linden tree saplings in the garden. And you know, I pulled them out and replanted them next to the wall. He’s a grouch. A tough guy. An old solider. Graduated from two university faculties. He’s a pharmacist too. He had an important job for years in a hospital. He’s from Izmir.”

I saw the old doctor’s wife close up for the first time.

We couldn’t figure out exactly how old they were, but they must have been at least eighty. We offered them coffee. We had a nice chat.

The clarity of the doctor’s mind astounded us. He was telling us about things that had happened years ago, when he first came from Izmir to Ankara . . . the old Gülhane hospital, some of the streets in Ankara that were still dirt roads then, told us about the Ankara they had come to as a young couple, and about Izmir. He was a tall, thin man, the old doctor. His wife’s caretaker had slipped into a corner and was listening to what the doctor said.

His wife was silent. It was clear that she had once been a very beautiful woman.

The visit of these very old people had both surprised and pleased us.

Elfe said: “These are grand people; who knows how many years they’ve carried on, who knows what they’ve seen and been though in their lives? For people like them to just show up here out of the blue like that is both weird and somehow good fortune, a little bit of luck, if you ask me. Like swallows coming in from the balcony of an old mansion in spring and fluttering from here to there under the high ceiling . . .”

“Right,” I said. “Today’s an unusual day. What a different world these old people told us about. So, they’re from Izmir?”

“From Izmir. Both the doctor and his wife are from Izmir,” said Elfe.

I was amazed by the old doctor’s memory. He was the master of an older world, I felt it.

He spoke about old Izmir, of Alsancak, of Kordonboyu, and Kemeraltı.

IZMIR

I love this city; I know it like the palm of my hand. The place that makes me the most nostalgic is the Military Cemetery on Kadifekale. In this dynamic, lively city full of activity, I am profoundly affected by those silent, solemn tombstones, that organized state of death, the green shadows of the trees in the cemetery, and the fact that all these people removed from the world are now just a part of the earth, each but a name written upon a stone.

But Izmir is teeming with life. It’s like an uncontrollable, sexy woman. For me, Izmir is a woman preparing little meze snacks for her lover in front of a small window that looks out on the sea, cutting melon into slices and lining them up in a little boat-shaped plate, someone who doesn’t wear a bra under her thin print summer dress, with slightly plump arms, whose permanent has grown out, the blonde ends gathered at the back of her neck by a clip with gemstones on it, someone who has one or two thin gold bracelets on her arm, whose name might be something like Müzeyyen. Full of life, of hope, waiting at the window for her man, maybe sitting on his lap with her incredibly soft hips when he comes, someone who has the softness of the women from the old days, from childhood, a woman who occasionally hums a song, Müzeyyen.

Izmir. Izmir that I love so much. A boat slowly oozes its way across to Karşıyaka, as I sit sipping my tea in the little café at Pasaport.

Müzeyyen, you’re so beautiful at this time of the evening. I want to jump on the boat and go over to Karşıyaka; I want to get into the carriage of an old driver and clip-clop through the streets of Güzelyalı. I want the Gypsy fortuneteller in Susuz Dede (Thirsty Grandpa) Park, over by Fahrettin Altay’s place, to fling her beans down on the stone in front of me and say sweet lies that sound lovely to my ears.

The fortuneteller talks on her cell phone every once in a while. I look and see that the phone in her hand is not a bad model at all.

“Are you Esin Moralıoğlu?” she asks me. “I swear, you look just like her. Your hair’s so pretty.”

/> She tosses the stones in front of me.

“What’s this stone?”

“It’s Tayyip. It’s a good luck stone. The good luck stone came to you.”

I look at the fortuneteller’s face. It’s like charcoal. Black. Her hair has henna in it. She ties the scarf on her head on the side, and throws the beans, the tokens down in front of me again.

“What’s this one?” I say.

“It’s an old man,” she says. “He’s in love with you. He won’t give up. Girl, are you under a spell? There’s a spell on you. Give me a hundred liras, and I’ll break it.”

“I don’t want that, I don’t, I don’t want the spell to be broken!” I say.

The fortuneteller opens her eyes wide.

“Girl, are you crazy? They’ve got you all tied up. You don’t get to be with your lover . . . To get back together, to have your feet touch one another again . . . The man is old. But he has money . . . Wait a minute . . .”

“That’s enough,” I say.

I throw some money down in front of the Gypsy woman and stand up.

“You’re crazy,” says the woman. “All around you are mountains, stones, earth. Let me break it and you can let go and relax.”

“I like to live like that.”

“Really?”

“Really,” I say.

“I’ve never heard of people like you,” says the fortuneteller. “I’m here. If you change your mind, come back. I’ll break the spell, rip everything up. I’ll cut those ropes that bind you to pieces.”

I listen to her with interest.

“My soul is bound . . .”

“Let me release it, girl. What have I been saying to you?”

“Don’t change it. Leave it like this. Let me stay bound.”

I leave Susuz Dede Park.

Müzeyyen, you’re so beautiful! The bay sloshes around your plump white knees. In the sky, the bright half-moon has come out.

I could go mad. Everything all around me is so beautiful.

I’m a stranger in this city, actually. I don’t even have a place to stay. This is the old doctor’s city.

THE ZINCIRIYE HOTEL MARDIN

I closed the curtains in my room in the Zinciriye Hotel. There were colorful kilims on the floor, and in the corner a couch with brightly striped satin cushions on it. My bed had been turned down.

The Black Rose of Halfeti

The Black Rose of Halfeti